WASHINGTON & SANTA FE, NM (CBS) December 4, 2011 ― Two whistleblowers offer a rare window into the root causes of the subprime mortgage meltdown. Eileen Foster, a former senior executive at Countrywide Financial, and Richard Bowen, a former vice president at Citigroup, tell Steve Kroft the companies ignored their repeated warnings about defective, even fraudulent mortgages. The result, experts say, was a cascading wave of mortgage defaults for which virtually no high-ranking Wall Street executives have been prosecuted.

The following is a script of “Prosecuting Wall Street” which aired on Dec. 4, 2011. Steve Kroft is correspondent, James Jacoby, producer.

It’s been three years since the financial crisis crippled the American economy, and much to the consternation of the general public and the demonstrators on Wall Street, there has not been a single prosecution of a high-ranking Wall Street executive or major financial firm even though fraud and financial misrepresentations played a significant role in the meltdown. We wanted to know why, so nine months ago we began looking for cases that might have prosecutorial merit.

Tonight you’ll hear about two of them. We begin with a woman named Eileen Foster, a senior executive at Countrywide Financial, one of the epicenters of the crisis.

Steve Kroft: Do you believe that there are people at Countrywide who belong behind bars?

Eileen Foster: Yes.

Kroft: Do you want to give me their names?

Foster: No.

Kroft: Would you give their names to a grand jury if you were asked?

Foster: Yes.

But Eileen Foster has never been asked – and never spoken to the Justice Department – even though she was Countrywide’s executive vice president in charge of fraud investigations. At the height of the housing bubble, Countrywide Financial was the largest mortgage lender in the country and the loans it made were among the worst, a third ending up in foreclosure or default, many because of mortgage fraud.

It was Foster’s job to monitor and investigate allegations of fraud against Countrywide employees and make sure they were reported to the Board of Directors and the Treasury Department.

Kroft: How much fraud was there at Countrywide?

Foster: From what I saw, the types of things I saw, it was– it appeared systemic. It, it wasn’t just one individual or two or three individuals, it was branches of individuals, it was regions of individuals.

Kroft: What you seem to be saying was it was just a way of doing business?

Foster: Yes.

In 2007, Foster sent a team to the Boston area to search several branch offices of Countrywide’s subprime division – the division that lent to borrowers with poor credit. The investigators rummaged through the office’s recycling bins and found evidence that Countrywide loan officers were forging and manipulating borrowers’ income and asset statements to help them get loans they weren’t qualified for and couldn’t afford.

Foster: All of the– the recycle bins, whenever we looked through those they were full of, you know, signatures that had been cut off of one document and put onto another and then photocopied, you know, or faxed and then the– you know, the creation thrown– thrown in the recycle bin.

Kroft: And the incentive for the people at Countrywide to do that was what?

Foster: The loan officers received bonuses, commissions. They were compensated regardless of the quality of the loan. There’s no incentive for quality. The incentive was to fund the loan. And that’s– that’s gonna drive that type of behavior.

Kroft: They were committing a crime?

Foster: Yes.

After Foster’s investigation, Countrywide closed six of its eight branches in the Boston region and 44 out of 60 employees were fired or quit.

Kroft: Do you think that this was just the Boston office?

Foster: No. No, I know it wasn’t just the Boston office. What was going on in Boston was also going on in Chicago, and Miami, and Detroit, and Las Vegas and, you know– Phoenix and in all of the big markets all over Florida.

After the Boston investigation, Foster says Countrywide’s subprime division began systematically concealing evidence of fraud from her in violation of company policy, and Countrywide’s internal financial controls system. Someone high up in the top levels of management – she won’t say who – told employees to circumvent her office and instead report suspicious activity to the personnel department, which Foster says routinely punished other whistleblowers and protected Countrywide’s highest earning loan officers.

Foster: I came to find out that there were– that there was many, many, many reports of fraud as I had suspected. And those were never– they were never reported through my group, never reported to the board, never reported to the government while I was there.

Kroft: And you believe this was intentional?

Foster: Yes. Yes, absolutely.

Foster, with the support of her boss, took the information up the corporate chain of command and to the audit department, which confirmed many of her suspicions, but no action was taken. In late 2008, with Countrywide sinking under the weight of its bad loans, it merged with Bank of America. Foster was promoted and not long afterwards was asked to speak with government regulators to discuss Countrywide’s fraud reports. But she was fired before the meeting could take place.

Kroft: What would you have told ’em?

Foster: I would have told ’em exactly– exactly what I’ve told you.

Kroft: Did you have any discussions with anybody at Countrywide or Bank of America about what you should say to the federal regulators when they came?

Foster: I got a call from an individual who, you know, suggested how– how I should handle the questions that would be coming from the regulators, made some suggestions that downplayed the severity of the situation.

Kroft: They wanted you to spin it and you said you wouldn’t?

Foster: Uh-huh (affirm).

Kroft: And the next day you were terminated?

Foster: Uh-huh (affirm).

Kroft: I mean, it seems like somebody at Countrywide or Bank of America did not want you to talk to federal regulators.

Foster: No, that was part of it, no, they absolutely did not.

Kroft: Do you feel like you were a victim of criminal activity?

Foster: It’s a crime to retaliate against someone for making reports of mail fraud, bank fraud, wire fraud, mortgage fraud, things that would harm stockholders and investors. And that’s what I did and that’s why I was terminated.

Kroft: Were you offered a settlement?

Foster: They asked me to sign a 14-page document that basically would buy my silence in exchange for a large amount of money.

Kroft: But you didn’t sign it?

Foster: No.

Kroft: Why not?

Foster: How many people can they– can they buy off? They just pay for it. They commit the crime and they buy their way out of it. And just do it over and over and over again. I wanted them to have some sleepless nights thinkin’ about what they would say to a federal investigator and worry about being exposed and being held accountable for committing a crime.

Eileen Foster spent three years trying to clear her name. This fall she finally won a federal whistleblower complaint against Bank of America for wrongful termination and was awarded nearly a million dollars in back pay and benefits.

All of this raises several questions. Why has the Justice Department failed to go after mortgage fraud inside Countrywide? There has not been a single prosecution. Even more puzzling is the Justice Department’s reluctance to employ one of its most powerful legal weapons against Countrywide’s top executives. It’s called the Sarbanes Oxley Act of 2002.

It was overwhelmingly passed by Congress and signed by President Bush following the last big round of corporate scandals involving Enron, Tyco and Worldcom. It was supposed to restore confidence in American corporations and financial markets.

The Sarbanes Oxley Act imposed strict rules for corporate governance, requiring chief executive officers and chief financial officers to certify under oath that their financial statements are accurate and that they have established an effective set of internal controls to insure that all relevant information reaches investors. Knowingly signing a false statement is a criminal offense punishable with up to five years in prison.

Frank Partnoy is a highly regarded securities lawyer, a professor at the University of San Diego Law School and an expert on Sarbanes Oxley.

Frank Partnoy: The idea was to have a criminal statute in place that would make CEOs and CFOs think twice, think three times before they signed their names attesting to the accuracy of financial statements or the viability of internal controls.

Kroft: And this law has not been used at all in the financial crisis.

Partnoy: It hasn’t been used to go after Wall Street. It hasn’t been used for these kinds of cases at all.

Kroft: Why not?

Partnoy: I don’t know. I don’t have a good answer to that question. I hope that it will be used. I think there clearly are instances where CEOs and CFOs– signed financial statements that said there were adequate controls and there weren’t adequate controls. But I can’t explain why it hasn’t been used yet.

We told Partnoy about Eileen Foster’s allegations of widespread mortgage fraud at Countrywide and efforts to prevent the information from reaching her, the federal government and the board of directors in violation of the company’s internal controls.

Kroft: I mean, that’s a deliberate circumvention, right?

Partnoy: It certainly sounds like it. And it certainly sounds like a good place to start a criminal investigation. Usually when the federal government hears about facts like this, they would start an investigation and they would try to move up the organization to try to figure out whether this information got up to senior officers, and why it wasn’t disclosed to the public.

In fact, according to a civil suit filed by the Securities and Exchange Commission, Countrywide’s chief executive officer, Angelo Mozilo, knew as early as 2006 that a significant percentage of its subprime borrowers were engaged in mortgage fraud and that it hid this and other negative information about the quality of its loans from investors.

When the case was settled out of court a year ago October, the SEC’s director of enforcement, Robert Khuzami, called Mozilo “a corporate executive who deliberately disregarded his duty to investors by concealing what he saw from inside the executive suite — a looming disaster in which Countrywide was buckling under the weight of increasing risky mortgage underwriting, mounting defaults and delinquencies, and a deteriorating business model.”

Mozilo, who admitted no wrongdoing, accepted a lifetime ban from ever serving as an officer or director of a publicly traded company, and agreed to pay a record $22 million fine, less than five percent of the compensation he received between 2000 and 2008.

Kroft: What did you think of the settlement with Countrywide?

Partnoy: I’d think a lot of it if I were Angelo Mozilo. I’d think I did pretty well for myself. No jail, a relatively small fine compared to the hundreds of millions of dollars I was able to take out of this company.

Kroft: Slap on the wrist.

Partnoy: Clearly a slap on the wrist. And part of the problem is the dual nature of how we prosecute these kinds of violations. We have the Department of Justice, which can put people in jail and the Securities and Exchange Commission, which can’t. And its sort of like we have this two-headed monster – one head has some teeth. The other head has no teeth. And it was the head with no teeth that went after Angelo Mozilo. So the greatest danger he was in from the beginning was maybe he’d be gummed to death, but not even that happened.

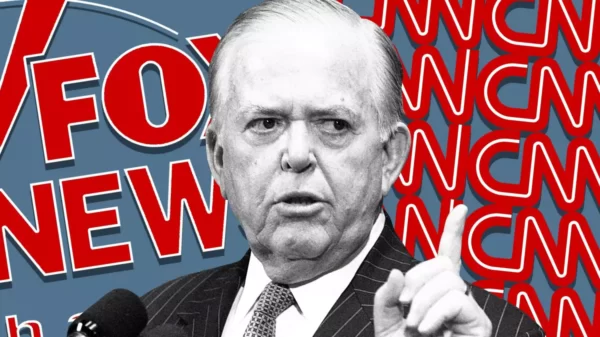

Three months after the SEC settled the civil suit, federal prosecutors in Los Angeles dropped their criminal investigation of Countrywide and its CEO, Angelo Mozilo. We wanted to know why the Justice Department has been unable to bring a single criminal case against Countrywide or any of the major Wall Street banks and Lanny Breuer, the head of the criminal division at the Justice Department, agreed to talk to us.

Kroft: A year ago, in September of 2010, you told the congressional hearing that you seek to prosecute people who make materially false statements. People who told the investors one thing and did something different.

Lanny Breuer: That’s absolutely right. And we’re– we’re doing exactly that.

Kroft: We spoke to a woman at Countrywide, who was a senior vice president for investigating fraud. And she said that the fraud inside Countrywide was systemic. That it was basically a way of doing business.

Breuer: Well, it’s hard for me to talk about a particular case. Of course, in the Countrywide case, Steve, as you know, terrific office, U.S. attorney’s office in Los Angeles investigated that, interviewed many, many people, hundreds of people perhaps, and reviewed millions of documents.

Kroft: They never talked to the senior vice president inside Countrywide, who is charged with investigating fraud.

Breuer: Well, I– we– look, I– I can’t speak about that, because I actually don’t know about that particular case. But if the senior vice president of any company believes they know about fraud, I want them to contact us.

Breuer says the department has brought major financial prosecutions involving hedge funds, insider trading, Ponzi schemes and a huge bank fraud case in Florida but he acknowledged there have been no prosecutions against major players in the financial crisis.

Breuer: In our criminal justice system, we have to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that you intended to commit a fraud. But when you can’t or when we think we can’t, there’s still many, many important resolutions and options we have.

And that’s why there have been civil lawsuits and regulatory action.

Kroft: Do you lack confidence in bringing cases under Sarbanes Oxley?

Breuer: Steve, no– no one is– really has accused this Department of Justice or this division or me of lacking confidence. If you look at the prosecutors all over the country, they are bringing record cases, with respect to all kinds of criminal laws. Sarbanes Oxley is a tool, but it’s only one tool. We’re confident. We follow the facts and the law wherever they take us. And we’re bringing every case that we believe can be made.

Lanny Breuer says this Justice Department has been as aggressive as any in history. But a recent report on federal prosecutions from a research center at Syracuse University, says the number of cases brought against financial instutions for fraud is at a 20-year low. When we come back, we talk to a whistleblower who was inside Citigroup during the financial meltdown.

If you had looked at the financial statements of the major banks on Wall Street in the weeks leading up to the financial crisis of 2008, you wouldn’t have guessed that most of them were about to crumble and require a trillion dollar bailout from the taxpayers. It begs the question did the CEO’s of these banks and their chief financial officers withhold critical information from their investors. If they did they can be subject to criminal prosecution under the Sarbanes Oxley Act for knowingly certifying false financial reports and statements about the effectiveness of their internal controls. The Justice Department has not brought a single case against Wall Street executives for violating Sarbanes Oxley, inspite of some compelling evidence. Tonight we take a look at Citigroup beginning with a former vice president, Richard Bowen.

Richard Bowen: There are things that obviously went on in this crisis, and decisions that were made, that people need to be accountable for.

Kroft: Why do you think nothing’s been done?

Bowen: I don’t know.

Until 2008, Richard Bowen was a senior vice president and chief underwriter in the consumer lending division of Citigroup. He was responsible for evaluating the quality of thousands of mortgages that Citigroup was buying from Countrywide and other mortgage lenders, many of which were bundled into mortgage-backed securities and sold to investors around the world. Bowen’s job was to make sure that these mortgages met Citigroup’s own standards – no missing paperwork, no signs of fraud, no unqualified borrowers. But in 2006, he discovered that 60 percent of the mortgages he evaluated were defective.

Kroft: Were you surprised at the 60 percent figure?

Bowen: Yes. I was absolutely blown away. This– this cannot be happening. But it was.

Kroft: And you thought that it was important that the people above you in management knew this?

Bowen: Yes. I did.

Kroft: You told people.

Bowen: I did everything I could, from the way– in the way of e-mail, weekly reports, meetings, presentations, individual conversations, yes.

Kroft: How high up in the company?

Bowen: My warnings, which were echoed by my manager, went to the highest levels of the Consumer Lending Group.

Bowen also asked for a formal investigation to be conducted by the division in charge of Citigroup’s internal controls. That study not only confirmed Bowen’s findings but found that his division had been out of compliance with company policy since at least 2005.

Kroft: Did the situation improve?

Bowen: I started raising those warnings in June of 2006. The volumes increased through 2007 and the rate of defective mortgages increased to an excess of 80 percent.

Kroft: So the answer is no?

Bowen: The answer is no, things did not improve. They got worse.

Not only was Citigroup on the hook for massive potential losses, Bowen says it was misleading investors about the quality of the mortgages and the mortgage securities it was selling to its customers. We managed to get our hands on a prospectus for a mortgage-backed security that was made up of home loans that Bowen had tested.

Kroft: It says, “These loans were originated under guidelines that are substantially, in accordance with Citi Mortgage’s guidelines, for its own originations, its own mortgages.” Is that a true statement?

Bowen: No.

Kroft: This is not some insignificant statement. This is– speaks to the quality of the– of the mortgages that– that investors are putting their money in.

Bowen: Yes.

Kroft: And it’s wrong?

Bowen: Yes.

Kroft: And people at Citigroup knew it was wrong. Had been warned that it was wrong, had been told that it was wrong.

Bowen: Yes.

In early November of 2007, with Citi’s mortgage losses mounting, Bowen decided to notify top corporate officers directly. He emailed an urgent letter to the bank’s chief financial officer, chief risk officer, and chief auditor as well as Robert Rubin, the chairman of Citigroup’s executive committee and a former U.S. treasury secretary. The letter informed them of “breakdowns of internal controls” in his division and possibly “unrecognized financial losses existing within our organization.”

Kroft: Why did you send that letter?

Bowen: I knew that there existed in my area extreme risks. And one, I had to warn executive management. And two, I felt like I had to warn the Board of Directors.

Kroft: You’re saying there’s a serious problem here, you’ve got a big breakdown in internal controls. You need to pay attention. This could cost you a lot of money.

Bowen: Yes. Somebody needed to pay attention. Somebody needed to take some action.

The next day Citigroup’s CEO Charles Prince, in his last official act before stepping down, signed the Sarbanes Oxley certification endorsing a financial statement that later proved to be unrealistic and swore that the bank’s internal controls over its financial reporting were effective.

Bowen: I know that there were internal controls that were broken. I served notice in that e-mail that they were broken. And the certification indicates that they are not broken.

Kroft: It would seem the chief financial officer and the people that signed the Sarbanes Oxley certification disregarded those warnings.

Bowen: It would appear.

We received a letter from Citigroup saying the bank had acted promptly to address Richard Bowen’s concerns and that the issues he raised were limited to his division and had little bearing on the bank’s overall financial health. Citigroup also told us that it did not retaliate against Bowen for sending the email. But not long after he sent it, Bowen’s duties were radically changed.

Bowen: I was relieved of most of my responsibility and I no longer was physically with the organization.

Kroft: You were told not to come into the office?

Bowen: Yes.

[Phil Angelides: Mr. Bowen.

Bowen: I am very grateful to the commission to be able to give my testimony today.]

The Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission thought enough of Bowen’s story to call him as one of its first witnesses and he turned over more than a thousand pages of documents to the Securities and Exchange Commission. Nothing ever came of it. But Bowen wasn’t the only one to warn Citigroup’s top officials about its financial weaknesses and breakdowns in the company’s internal controls.

Three months after Bowen’s email Citigroup’s new CEO Vikrim Pandit received a blistering letter from the office of the comptroller of the currency, its chief regulator. It questioned the valuations that Citi had placed on its mortgage securities and found internal controls deeply flawed. The letter stated, among other things, that risk management had insufficient authority and risk was insufficiently evaluated and that the Citibank board had no effective oversight.

Yet eight days later, CEO Vikrim Pandit and Chief Financial Officer Gary Crittenden personally signed the Sarbanes Oxley certification. They attested to the bank’s financial viability and the effectiveness of its internal controls. The deficiencies cited by the comptroller of the currency were never mentioned. Citi said it didn’t consider the problems serious enough that they had to be disclosed to investors and says the certifications were entirely appropriate. But nine months later, Citigroup would need a $45 billion bailout and $300 billion more in federal guarantees just to stay in business.

Frank Partnoy: I don’t think Wall Street senior people really think they’ll ever end up in jail and they’ve been right.

Frank Partnoy, the securities lawyer and expert on Sarbanes Oxley law, says the facts about Citigroup raise some troubling questions.

Partnoy: They certainly knew the internal controls were inadequate and that the company was out of control from a reporting perspective.

Kroft: And yet they signed the Sarbanes Oxley letter saying that everything was fine.

Partnoy: I’m very surprised that the CEO and CFO would sign those letters. I wouldn’t have signed them under those conditions. You’re signing them under penalties of potentially 10 years in prison. You’re certifying that you designed and implemented effective internal controls in the aftermath of all this news about the company’s problems.

Kroft: How is that not a violation of Sarbanes Oxley?

Partnoy: I don’t know. I think that it might be hard to establish knowledge. That might be what prosecutors are thinking in not bringing the cases.

Kroft: The letter was addressed to Vikram Pandit, the new CEO of Citigroup.

Partnoy: And he had eight days to think about it, from February 14th, Valentine’s Day, he gets the letter. And then February 22nd, he sits down and signs his name, certifying that financial statements are accurate and that he had designed and evaluated and reported any problems with internal controls. Eight days is a long time on Wall Street. I can’t get inside his head, but I would certainly think, as a prosecutor, that this would be something I’d be interested in asking some questions about.

We wanted to know what Assistant Attorney General Lanny Breuer, thought about that, and why no prosecutions have been directed at Wall Street. We also wanted to know why Sarbanes Oxley has not been used against big banks like Citigroup.

Lanny Breuer: When you talk about Sarbanes Oxley we have to know that you intended– had the specific intent to make a false statement.

Kroft: They knew there was a problem. Not only had they been told that there was a problem by one of their chief underwriters, that the loans that they were buying were not what they claimed, and that the federal government, that the comptroller of the currency didn’t think their internal controls were adequate either.

Breuer: If a company is intentionally misrepresenting on its financial statements what it understands to be the financial condition of its company and makes very real representations that are false, we want to know about it. And we’re gonna prosecute it.

Kroft: Do you have cases now that you think that will result in prosecution against major Wall Street banks?

Breuer: We have investigations going on. I won’t predict how they’re gonna turn out.

Kroft: Has anybody at Treasury or– or the Federal Reserve or the White House come to you and said, ‘Look, we need to go easy on the banks. That– there are collateral consequences if you bring prosecutions. Some of these organizations are still very fragile and we don’t want to push them over the edge?’

Breuer: Steve, this Department of Justice is acting absolutely independently. Every decision that’s being made by our prosecutors around the country is being made 100 percent based on the facts of that particular case and the law that we can apply it. And there’s been absolutely no interference whatsoever.

Kroft: The perception. I mean, it doesn’t seem like you’re trying. It doesn’t seem like you’re making an effort. That the Justice Department does not have the will to take on these big Wall Street banks.

Breuer: Steve, I get it. I find the excessive risk taking to be offensive. I find the greed that was manifested by certain people to be very upsetting. But because I may have an emotional reaction and I may personally share the same frustration that American people all over the country are feeling, that in and of itself doesn’t mean we bring a criminal case.

Kroft: If you had said two years ago that nobody was gonna be prosecuted on Wall Street for the subprime mortgage scandal, I think people would think, “It’s not possible.”

Breuer: Sometimes it takes a number of years to bring these cases. So I’d say to the American people, they should have confidence that this is a department that’s working hard and we’re gonna keep working hard, so stay tuned.