ABILENE (By Brian Bethel, Scripps News) November 1, 2009 ― Joe Alcorta doesn’t believe in La Llorona.

But growing up for a time in Mexico, Alcorta, like many, soon became familiar with shivery tales of the spectral woman who haunts waterways and lonely places, searching for children — in some variations — she herself drowned.

“I grew up in Mexico my first seven or eight years,” said Alcorta, who was born in the United States. “Everyone talks about La Llorona, La Llorona. And that’s how parents a lot of the time — it’s kind of bad — scare their children: ‘If you don’t behave, La Llorona is going to come and get you.’ ”

From the fall of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan to the present day, the weeping, ghostly figure has long haunted Hispanic folklore.

Scholar Roseanna Mueller, who teaches at Columbia College in Chicago, said at its basic level, the tale serves as an effective foil against willful children who might otherwise get into mischief. Versions of the story are common to Mexico and Central and South America.

But the ghastly figure has become in many ways much more than a way to scare young people straight, permeating oral legend, literature, song, film and popular media, Mueller wrote in her “La Llorona, The Weeping Woman: The Sixth Portent, the Third Legend.”

Though he has long left such fears behind, and doesn’t believe in ghosts, even Alcorta recalls being scared by the story.

Such was a circumstance that might require one’s mother to “cure” you of being frightened by swept with a broom accompanied by the recitation of Catholic prayers to “scare the evil spirit away,” he said.

These days, Alcorta and many others who grew up hearing the stories respond with a more bemused air.

“I don’t think she exists,” Alcorta said. “But there are people who swear up and down that they saw her.”

And as it turns out, people have been claiming that for a very long time.

Enduring Power

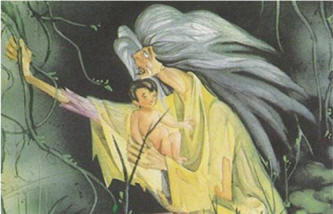

Although there is disagreement about the exact origin of the legend, the La Llorona tale inevitably involves a female phantom who can be heard, although seldom seen, weeping and wailing, often for children she herself has destroyed.

The idea of a woman murdering her own children is something that inspires horror in many cultures, Mueller said.

Motivations for the murders vary from vengeance for the husband who deserted her, the concealment of an illegitimate birth, the choice to see her children die a swift death rather than to witness their prolonged suffering, and others, Mueller said.

In some versions, La Llorona is not a murderer but simply negligent, while in others she is a blameless figure whose children die in a tragic accident.

It is because of the drowning aspect of many stories that her doomed wanderings, accompanied by horrific wailings, are often set near bodies of water — useful for parents to warn children away from lakes, rivers and streams.

In another version of the story, “La Llorona of the Moon,” the phantom emerges on the first night of the full moon to gather evil souls.

In some stories, though the weeping woman is a temptress, luring men into following her with tragic consequences — a version that provides a possible link to pre-Columbian sources, namely the Aztec deity Cihuacoatl or “Snake Woman.”

The legend is also associated with the conquest of Mexico, Mueller said, with both the “Codex Florentino” and Munoz Camargo’s “Historia de Tlaxcala” include a wailing woman as the sixth omen or portent that predicted the fall of Tenochtitlan.

“It was reported that on the eve before the fall of the Aztec capital, a woman was heard crying, sobbing and sighing throughout the night, asking what would become of her children,” Mueller wrote in her examination of La Llorona as a cultural phenomenon.

Also read: Why Cuban Americans Vote Republican

A sonnet written in the second half of the 19th century by the Mexican poet Manuel Carpio may be the earliest published reference to the wailing spirit, who is also mistakenly sometimes identified as the remorseful ghost of Dona Marina, or La Malinche, explorer Hernan Cortés’ mistress and interpreter, by whom she had a child.

It was erroneously reported that Malinche had killed this child, Mueller said.

La Malinche, who had learned to speak Spanish, warned Cortes of several plans to destroy the Spanish army.

“In this instance, Dona Marina’s association with La Llorona reinforces Malinche’s role as betrayer to the Mexican people, thus raising larger issues of loyalty and ethnic identity,” Mueller wrote.

Along with La Malinche, who represents the betrayer of her people, and the Virgin of Guadalupe, who is considered the Second Eve and redeeming mother, La Llorona forms part of “the Third Legend” of Mexico, Mueller said.

“La Llorona is the subversive phantom woman whose tale is largely transmitted through oral narrative by women,” she said.

The story has seen some revisions as time has gone on, with some benevolent — and sympathetic — versions of the weeping woman coming on the scene, while feminists have re-examined the basis of the legend and come to interpret the tale as “populist propaganda intended to reinforce the patriarchy,” according to Mueller’s essay.

“In all versions, the father of the dead children suffers no consequences while the woman gets punished for her sin of sexual gratification or female subversion,” Mueller said.

In Mueller’s opinion, the legend persists because its variations reflect everyday reality, with modern teenagers incorporating elements of the folk tale into ghost stories that use real neighborhood references.

Hardin-Simmons University Spanish teacher Teresia Taylor said in an e-mail that she has known about La Llorona “as long as I remember.”

During trips between San Diego and Freer and then on to Laredo, Taylor remembers being afraid of being out close to dark because La Llorona “might be hitchhiking.”

She remembers expecting to see or hear the Weeping Woman hanging out at a plaza she and others used to skate at as preteens across from a nearby Catholic church.

“Like all children, we spooked each other and ran and squealed if we heard an unfamiliar sound — very sure that she needed a child and it might just be one of us,” Taylor said.

Sara Casselberry, 25, grew up hearing stories of La Llorona extending from her father’s side of the family.

“That used to scare my brother and I when we were little,” she said. “The wind blows, and it kind of sounds like howling and you think ‘oh my gosh, she’s going to come steal us’ or something like that.”

Later, she recalls reading about the story in fifth or sixth grade and being somewhat surprised that there were actually others who knew the legend.

Later, Casselberry, now an adjunct English instructor at Hardin-Simmons University, used the story as the seed of a poem.

She had read a news story about parents, in the United States illegally, who were later deported but forced to leave their children behind.

“I immediately thought of the weeping woman,” she said. “This was sort of the real life counterpart, where there were women in Mexico who were weeping for their children here in Texas.”

No matter which version one is familiar with, Casselberry said the story is one that doesn’t easily leave the hearer.

“It’s very, very strange and unsettling,” she said.

But she said she’s not sure how an Internet-savvy Hispanic culture will interface with the narrative in the future, especially when it’s easy to debunk such tales using common research tools.

“I don’t know if it will have the same effect,” she said. “But I think the story is still going to keep going because it’s so intriguing.”

And though Casselberry no longer worries about being kidnapped by the wailing ghost, she acknowledges, like Alcorta, that there are still “many people who think she’s out there.”

Alcorta, too, said he still receives the occasional, perhaps tongue-in-cheek warning.

“We have a home in Breckenridge, and of course we’ve been going to Breckenridge for probably the last 50 years or so,” he said. “And I would hear people say to be careful coming back through Albany because a lot of people have seen La Llorona.”

Apparently, the ghost likes the hills thereabouts.

“She’s hiding out there,” Alcorta said. “So that’s the deal, you know?”